What is Asherman’s Syndrome?

Asherman’s syndrome is a condition in which adhesions or scar tissue develop inside the uterus, sticking the front wall to the back wall of the uterus, obstructing or obliterating the endometrial cavity where a pregnancy develops.

Asherman’s syndrome usually develops after a surgical procedure on the uterus such as a D&C (Dilatation and curettage), termination of pregnancy, evacuation of retained products of conception after a miscarriage or retained placenta or more extensive surgery such as a myomectomy (operation to remove a fibroid). It is usually made worse if there is an infection, and is much more common than many doctors accept. It is not always caused by poor surgical technique and is an unfortunate but inevitable consequence of some procedures. It is often easier to deal with the condition if it is anticipated and treated early. The adhesions can sometimes become fibrous and more mature and therefore more difficult to manage if it is left untreated.

How do you know you have Asherman’s syndrome?

Asherman’s Syndrome symptoms. Most women with Asherman’s syndrome will notice that their periods become much lighter than they were before the operation and sometimes the periods stop altogether. Many women also experience significant cramping and pain at the expected time of their period, especially if they don’t see any loss at all.

How Common is Asherman’s Syndrome?

Asherman’s syndrome is much more common than many doctors think and many do not consider the diagnosis as a result. The estimates of the proportion of D&C procedures that cause it vary from less than 1% to up to 5%. The incidence is much higher following miscarriage and retained placenta. If you have had surgery and your periods are lighter than they were before it is certainly worth checking it out.

How is Asherman’s Syndrome diagnosed?

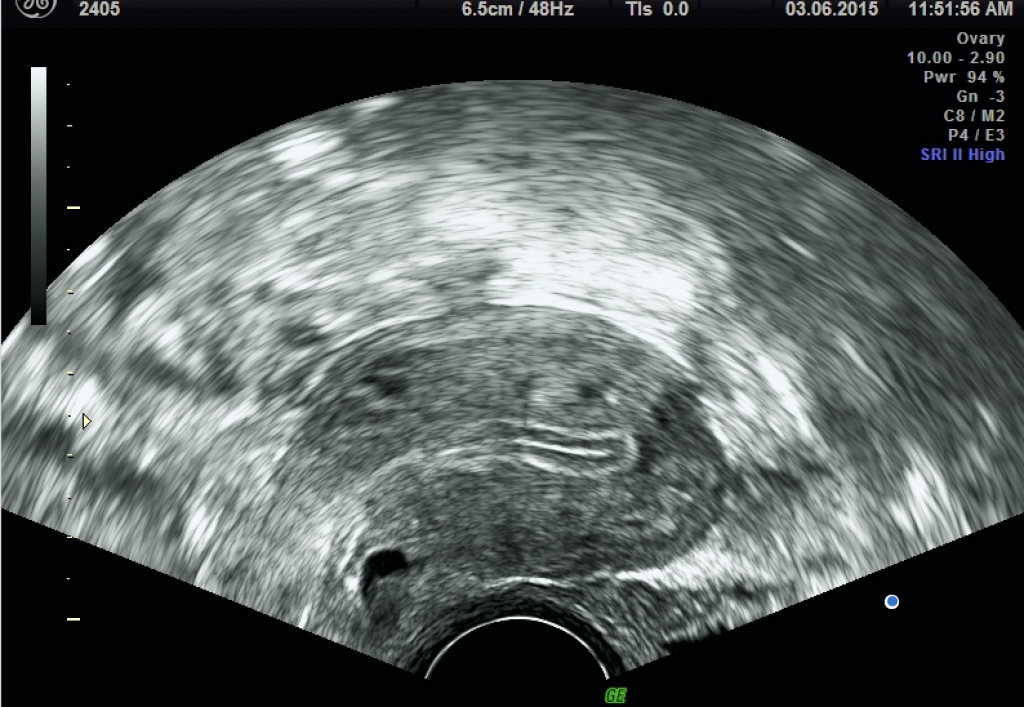

Asherman’s syndrome diagnosis is usually made on the history of lighter or absent periods often with cyclical pain. It can be confirmed by a 3D transvaginal ultrasound scan, saline infusion sonogram, hysterosalpingogram or hysteroscopy.

The 3D transvaginal ultrasound scan probe is able to use higher-frequency sound waves improving the resolution of the images obtained. Some care needs to be exercised in relying on endometrial thickness to make a diagnosis of Asherman’s syndrome.

The endometrial thickness varies throughout the menstrual cycle. The maximum thickness is usually found around mid-cycle, before ovulation. After ovulation, the corpus luteum on the ovary will start to produce progesterone which causes condensation of the endometrium resulting in thinner measurement at ultrasound.

How does Asherman’s Syndrome affect fertility?

In the worst case, Asherman’s syndrome can affect fertility by obliterating the cavity so there is nowhere for the embryo to develop, or it can make the endometrium so thin that implantation cannot occur. Adhesions can also block off the Fallopian tube or the cervix so that sperm cannot gain access to the egg to fertilise it.

Severe scarring can also affect the elasticity of the endometrium and limit the ability of the uterus to accommodate the growing fetus.

Many women will go on to conceive naturally after Asherman’s syndrome has been successfully treated. Some will require assisted conception either to speed up the time to conception (especially for older patients) or in cases of recurrent miscarriage where it may be important to eliminate the risk of another miscarriage due to aneuploidy (abnormal numbers of chromosomes such as Trisomy 21 or Downs syndrome).

How is Asherman’s Syndrome treated?

Treatment of Asherman’s syndrome aims at restoring the size and shape of the uterine cavity, preventing recurrence of the adhesion, promoting the repair and regeneration of the destroyed endometrium, and restoring normal reproductive functions.

The intrauterine adhesions are identified and treated by hysteroscopy using microscissors to divide the adhesions. It is best if this procedure is done by a surgeon who has plenty of experience in treating Asherman’s syndrome, since it can be made much worse if the hysteroscope is introduced in the wrong place, creating a false passage which is surprisingly easy to do. Our experienced surgeons at the Asherman’s Syndrome Surgical Centre do this under xray or ultrasound control to ensure that they are in the true cavity of the uterus.

Unfortunately the adhesions can come back and it is essential to have high dose oestrogen treatment to encourage regrowth of the endometrium after the adhesions have been divided to reduce this risk. A stent or contraceptive coil is also often left in the uterus to help to prevent adhesions from regrowing and to break them down when the coil is removed.

The prognosis for most women with Asherman’s syndrome is good and we can improve the uterus in most cases. Sometimes however the uterus is so badly damaged that the endometrium has been completely lost. In these cases the only option is to resort to surrogacy.

Over the last century, many surgical techniques have been described. For the sake of completeness we list some of them here.

Expectant Management – In other words do nothing except watch and wait. In some cases the damage will repair spontaneously, especially if there is an isolated blockage in the cervical canal when cramping in the uterus can result in breaking down the adhesion and the restoration of menstruation. We do not usually recommend adopting this strategy for more than 2 or 3 months, as the longer you wait for menstruation to return, the more likely it is that dense fibrous adhesions will form. Most patients reaching us have waited considerably longer than 2 or 3 months.

Hysteroscopic surgery is the gold standard and it is our practice to use scissors. Some surgeons use various energy sources to lyse the adhesions. These include laser, diathermy, Versapoint and the myosure device, which was originally designed for removal of small submucous fibroids and polyps. We do not advocate the use of energy sources as it is difficult to predict how far the energy will extend into the deeper tissues where unseen damage can occur leading to further fibrosis. Also there is no tactile feedback to the surgeon as the tissue is divided. If concurrent transabdominal ultrasound scanning is not employed it is possible to create a false cavity as the energy is quite powerful and cuts through normal uterine tissue just as easily as it does through adhesions.

The Myosure device is extremely useful for removing dense fibrous plaques of retained products of conception or mature fibrous adhesions after the cavity has been opened. Care must be taken not to completely remove the basal layer of endometrium from which new endometrium will regrow.

Precautions whilst performing hysteroscopy

– Scarring and tortuous cervical canal.

– U/s control and HSG

– Endometrial fibrosis

– Marginal adhesions are often missed. Difficult to identify

How will I know if surgery has been successful?

In the majority of cases surgery results in restoration of normal periods and elimination of pain at the time of menstruation. Often the periods are not as heavy as they were before the original injury and it can take some months before the endometrium grows back.

Second look hysteroscopy

Sometimes a second look hysteroscopy is required, especially if the adhesions are very extensive or there is a lot of fibrosis. This can sometimes be done as an outpatient procedure in the office. We can also perform saline infusion sonogram as a proof of cure.

What are the long term complications

The main risk is recurrence of adhesions. The use of high dose oestrogen therapy, stents and/or IUCD can help to reduce this. Sometimes a further surgical procedure may be required.

Later complications include:

Retained placenta – Asherman’s syndrome can be caused by abnormalities of separation of the trophoblast (placenta and membranes) from the endometrium. Although adhesions can be removed these abnormalities may persist in a subsequent pregnancy, and the placenta may not separate and cannot be delivered normally. A manual removal may then be required with attendant risk of severe haemorrhage and of course further adhesions subsequently. This effect may be exacerbated by areas of thin and dysfunctional endometrium following surgery.

Cervical incompetence – this is associated with Asherman’s syndrome but may not be caused by the condition or the surgery to correct it. The use of modern narrow gauge instruments removes the need to dilate the cervix, however many women suffer with Asherman’s syndrome have experienced multiple miscarriages with repeated cervical dilatation to 9mm or more. This can weaken the cervix and cause it to shorten. Regular tranmsvaginal ultrasound scans in the later first trimester and mid trimester of pregnancy can identify a shortening cervix allowing early intervention with cervical cerclage.

Recurrent miscarriage – Although the major adhesions between the walls of the uterus may be removed satisfactorily, the endometrium can remain thin and may result in poor implantation leading to recurrent miscarriage. Recurrent miscarriage may also be the casue of the Asherman’s syndrome especially if multiple ERPCs have been performed. It is our practice to investigate fully for potentially treatable causes of recurrent miscarriage once we have dealt with the adhesions. In older women where the rate of aneuploidy (abnormal numbers of chromosomes in the fetus) is higher we also recommend IVF with pre- implantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) which eliminates the risk of miscarriage due to aneuplody, one of the most common causes of miscarriage. This does require good ovarian reserve to be effective. Further information about IVF with PGT-A can be found on our sister website here

Obstetric complications – The placenta is vital to pass nutrients and oxygenated blood to the developing fetus. Scarring of the endometrium may reduce the efficiency of this process as well as increasing the risk of retained placenta. This may increase the risk of small for gestational age babies and necessitate early delivery.

Infection – Infection often increases the severity of the adhesions found with a surgical insult leading to Asherman’s syndrome. Multiple surgical procedures also increase the risk of intrauterine infection. This may result in a dysbiosis (disturbance of the natural bacterial environment in the endometrium) or chronic endometritis. We usually recommend an endometrial biopsy to look for signs of infection after treatment if there is a delay in conceiving or the endometrium fails to develop satisfactorily. On occasion, empirical treatment with antibiotics and vaginal probiotics may be worth trying.